The subject is health, the meaning of health for the human being and race

by Hanne Campos

2002

This investigation was carried out in group, a multidisciplinary group of colleagues from the disciplines of psychology, sociology, philosophy, history and anthropology, medicine and nursing. We called it the Articulating Group since its principal task was to try and find ways of articulating the different discourses in relation to health. The group met during five years and a half, twice a month, in a room made available by the Faculty of Sociology of the University of Barcelona. Throughout the experience the size of the group varied from 6 to 10 members.

To the investigation also contributed the so-called Groups of Experience, groups in the place of work of some of the members of the Articulating Group with which we tried to share the ideas generated and tried out the benefit of the latter in the day to day practice.

Since the university does not admit group theses, I presented it as spokesman of the Articulating Group, although, of course, I am the ultimate responsible for the organization and interpretation of the material.

The First Chapter is about the ideas of health in the twentieth century. During this period a new conscience emerges. We become conscious of the relationship between individual health and social health and that one does not exist without the other.

There occurs a displacement from an individual approach to health towards propositions that include the natural and socio-cultural contexts. These new propositions entail different explanations of one and the same phenomenon and require the articulation between different theories and disciplines.

Also, we start to consider health as a process more than a state; a process related to the quality of life, to what we consider normal, tolerable, curable or desirable in a determined social context and historic moment.

These new ways of thinking about health and the new methods in health care and education are summarized in the following maxim: “Think globally, act locally”. Prevention and education complement each other to preserve, to accomplish or to reestablish a harmonious equilibrium between biological conditions and social and cultural requirements of human life.

Also, we become conscious of the importance of language itself, of the intellectual and emotional impact of thinking and saying things in a specific way. In the last century, a ‘linguistic turn’ takes place. All disciplines develop their own languages, a change which entails a progressive specialization and technification of knowledge and creates the urgent need of a comprehensive, global view.

The thesis seeks to investigate health beyond physical ill-health, in the wider context of the meanings we give to experience. It is in the universe of meaning that malaise is generated. To give meaning makes us feel well, gives us the feeling of unity and of completeness. But every time we create a meaning, we also excluded parts that are left out. These schisms form an inevitable part of the functioning of language and often produce discomfort in a person and between people.

The Second Chapter is about global theories that emerge together with this new conscience. The question is: ¿In what global frames of reference do and can these new and diverse ideas insert themselves?

The answers are produced in three lines of thought: 1. the concept of the whole, of the global whole; 2. the concept of system; and 3. the idea of change, that refers to dynamic relationship between the whole and his parts. These three conceptions happen to come from the context of biology, the source of change we call life. According to this thesis, the idea of change or rather the possibility of change, the conviction that things can change is an essential factor in the experience of health.

In the thesis I present authors and historic circumstances that give origin to these new ways of conceiving the human world. Goldstein, Selye and Bertalanffy are such names. The epoch is the decade of the thirties of last century.

The idea of totality implies: 1. the idea of the parts that compose it; 2. the idea of boundary that separate the parts from each other, and the totality from what it is not; and 3. the concepts themselves of totality, parts and boundary as result of a pre-conception about what in each case presents itself as figure and ground.

The idea of system, on the other hand, emerges because we begin to observe that there exist two classes of systems; some are closed in a stable state and others are open in a quasi-stable state that import from their surroundings materials which in turn they metabolize, as is the case of all human systems, which import energy in the form of food and information.

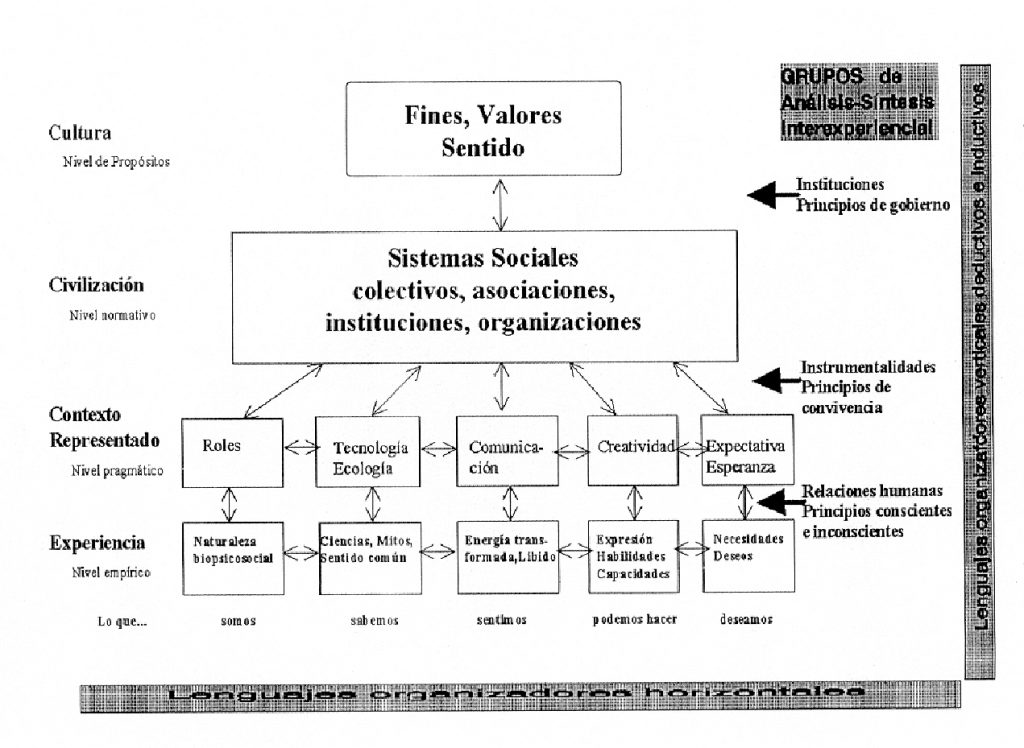

On occasion of this multidisciplinary work of the thesis, I remembered Erich Jantsch’s systemic scheme of the seventies, a part of his project carries the title “Education for Design”, referring to an education that includes its own redesign and continuous self organization”). Jantsch at that time was Associate of Investigation of the School of Public Health of the University of California at Berkeley.

Multi-echelon systems representation of total human experience and purposeful activity

Jantsch’s proposal evidences the innovations as much as the difficulties of a systemic conception.

There are three main innovations:

- The first has to do with the fact that systems theory is a constructive criticism of scientific linear-causal thought. It gives us new possibilities of posing problems which we habitually pose in a dichotomic way —black or white. The hierarchic organization of systems permits us to pose them in terms of dynamic differences —black-white.

- The second has to do with the question of change. Systems develop. The dynamics between the parts and the whole, and the whole and its surroundings, allow us to verify a direction or purpose. We can ask ourselves from where and in terms of what we decide or do not decide, the purpose, direction or self-regulation of a system. Besides, we recognize that the changes of the open systems are irreversible.

- The third invention has to do, once more, with language. The system par excellence is the one of language itself. The sub-systems take the form of languages and discourses organized in a characteristic way at different levels of human experience. This fact promotes a turn in the investigation of human systems that used to be carried out exclusively according to the models of natural sciences —physics, mathematics, statistics, etc.

There are two main difficulties:

- The propositions of general systems theory make a pedagogic reform inevitable, in reference to contents as well as training of professionals. Without the development of basic interdisciplinary principles, without the training of general scientists, without integrated studies, neither comprehension nor a global approach of human reality is possible.

- The systemic conception makes a systemic inter-experiential organization indispensable, as for assuring the possibility of change of consciousnesses and of cultures in terms of certain purposes, intentions and values.

In one of my papers of those years I investigate the sociological and psychological ideas of the concept of change. It so happens that both theoretic fields coincide in declaring that there are two types of change: a change “in” and a change “of”. The first one relates to reproductive processes within a system, the second to transformative processes of the system itself. In questions of health, sometimes it is enough to promote changes “in” the system —like taking out an appendix— and sometimes changes that concern the system itself are necessary —at present the family system being the most difficult.

In another of my papers I conceive of stress as the suffering of boundaries between the parts and the organismic whole, and the boundary itself as a conservative function of health. What we later call stress, Selye originally called it General Adaptation Syndrome. When stress is produced, what is threatened is the organism’s capacity of adaptation. It seems that in sociology the concept of progress has lately been replaced by the one of crisis —the kind of change inherent to the human agency. Stress as well as crisis used to be alarm signals of a failure of the capacity of adaptation of the whole organism. I am afraid that these alarm signals have become chronic and have made the individual as well as the social organisms inflexible and unable to adapt to changes.

The Third and Fourth Chapters are about methodology from the sociological and the psychological point of view. In the third chapter I look for supports and legitimations in sociology. In this chapter it becomes evident that my master was not in sociology. Bibliographic lagoons and repetitions appear in textual excerpts which I discover while preparing this presentation. Anyhow, I defend myself as follows. 1. The problems mentioned are inevitable in an interdisciplinary task. We should give ourselves permission to legitimately use references of different disciplines. 2. On the other hand, in the thesis only references and texts are used which the members of the Articulating Group in fact have brought to the group dialogue. This spontaneous selection permits us to become conscious and make a reading of the slants and limitations of transdisciplinary work. When we approach a problem collectively, we have experience and knowledge that the members bring to the group, which is not mince if we know how to use it. 3. As to the textual repetitions that I discovered when writing this presentation, these are evidence more of my methodological attitude than the identification with any specific techniques. For example, I subscribe to that the methodology in social sciences is a space of a continuous gradient of complexity which goes from the emphasis on technique to the emphasis on methodological and epistemological reflection. I would also agree in that praxis is the pragmatics of language itself, where the language is at the same time investigator and investigated in a specific context of communication. I was also glad to discover that recent methodologies in sociology integrate and take on board recent notions of physical sciences and cybernetics.

In relation to methodological devices I was glad to find the concepts of historical analysers and constructed analysers —instruments we create in a process of change—developed by Tomás Villasante with whom I met in 1996 in a Symposium —where the Articulating Group presented a paper— and who later on participated in a session of our group. Other devices relate to ideas of the well known psychoanalyst Winnicott, author of the idea of transitional object —the famous blanket of Linus that serves as “a witness of attachment” but also enables separation and differentiation. Something not so well known is that Winnicott also formulated the idea of transitional phenomena and transitional spaces like the how and where of transforming cultural experience. These to me seem useful concepts in work on an inter- and transdisciplinary level.

In the Fourth Chapter, for me a much saver territory, I inform on the group method of analysis. These feed the theoretical and practical bases of a group of analysis, although the group of analysis differs from the group method of analysis inasmuch as the latter presents itself mainly as an instrument of social investigation of the relation between individuals and groups on all levels of human experience.

I contribute the historical data. 1. The group methods of analysis emerge after the two World Wars, when for the first time the conflicts are conceived in “global” terms and global points of reference are much sought after also on other theoretical and practical levels, 2. They emerge beyond psychoanalysis, epigone of the thought centred in the individual. Also, right from the beginning it is clear that this step requires second-level changes, which after a century we still have not achieved. There exists a constant pressure of turning our thinking about groups into more or less totalitarian theories, useful in therapeutic tasks centred on individuals and carried out from the position of expert. 3. They carry the imprint of a connatural interdisciplinarity between psychology and sociology. Group methods of analysis are, in my opinion, an essential support in any transdisciplinary investigation whose structure, function and dynamics have to be taken into account as one more data of the investigation itself.

Chapters Five and Six are about the groups that support the investigation: The Articulating Group and Groups of Experience. The material generated is presented in 5 Appendix Sections.

In relation to the Articulating Group, Appendix A is a chronogram of the sessions, themes and general interchanges. Appendix B is an interpretation of the process in six stages. Appendix C includes documents specifically related to the inter- and transdisciplinary work of the Articulating Group. Appendix D presents the elaborations in terms of the scheme of Jantsch made by the Articulating Group

In relation to the Groups of Experience, Appendix E presents elaborations of the Groups of Experience in terms of the scheme of Jantsch.

Before sharing some data of the investigation in terms of the scheme of Jantsch, I advance certain conclusions of the investigation:

Villasante points out that: “It is not enough to give a voice to the subjects in question, rather it is necessary to create the conditions of a total exercise”. These conditions at present do not exist in our society. The following example gives testimony of this: During second stage, the Articulating Group’s task was becoming arduous. Just at that moment appear comments from the members about feeling somehow “marginal” in their places of work and impotent to change certain unhealthy practices. During those same days, the colleague dedicated to graphic design brings to the group a book on “theory and methodology of corporate image —reality, communication, identity and image”. This is right to the point. The Articulating Group does not have a social image. It does not have a place in the thought that contains and encompasses society as a whole. In terms of what global conception can we ask a commitment to interdisciplinary work? What social whole does the Articulating Group belong to? As long as the praxis of transdisciplinarity is not sustained by a group that does not reflect a split of part of the real and social whole, is not a representative group which is part of a real and social whole, transdisciplinarity in terms of a regular and continuous feedback between pragmática and praxis is not possible.

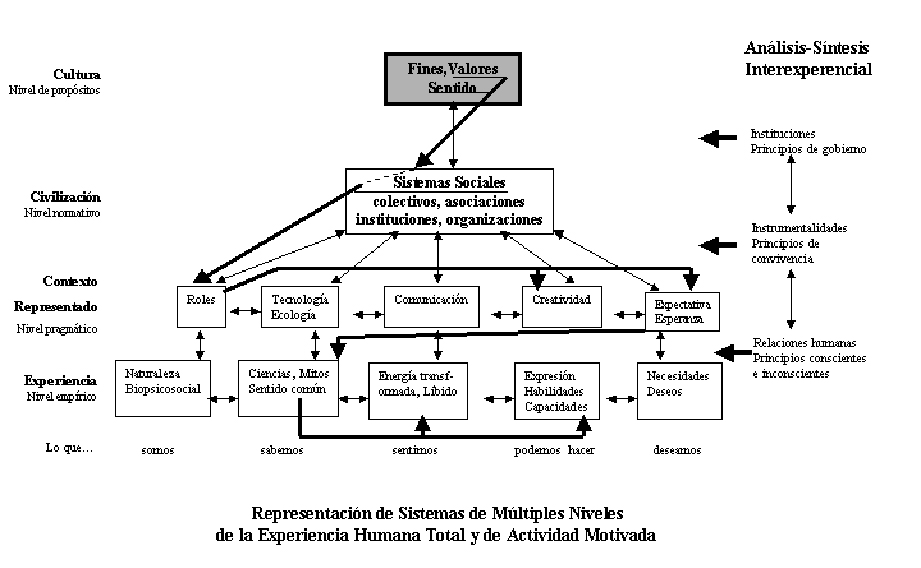

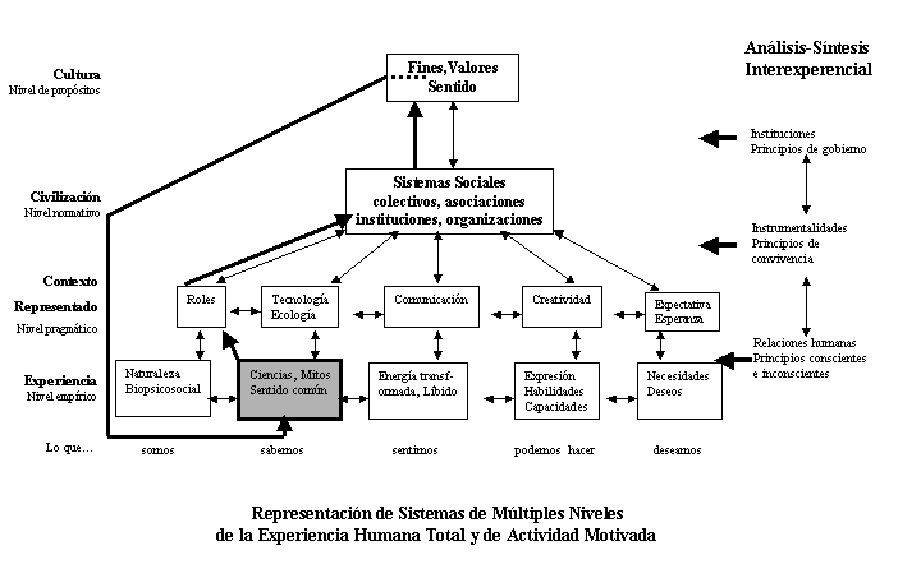

Nevertheless, Jantsch’s scheme can be useful in making headway as we go along. We made four investigations, one in the Articulating Group and three with the Groups of Experience. All in all, the investigation has 36 schemata completed by the participants, although on this occasion we only have enough time to take a look at a couple of schemata, as for example.

In the Articulating Group we used the scheme to make conscious the ideological factors in the professional positioning of each member of a group, starting from the suppositions that: 1. each professional discourse implies a model of the human being, an ideology and, in consequence, some ideas about what is healthy and what is not; 2. that we are responsible for the meanings we give to experience and collective life. “God is dead. Everything is allowed” is not acceptable. As professionals, and also in important situations of life, it is necessary that our reason is anchored in a specific point of the system that conditions our experience.

The instruction to the group was: “Choose one area and only one of the scheme as a starting point of your positioning in the Scheme II of Jantsch. Starting from this point, successively link the other locations you consider that they relate to your professional positioning. There can be places that do not link up “.

Examples Graphics 5.3 and 5.4. In the Graphic 5.3, for example, the author places herself starting from the objectives and values that successively influence the areas of the nearest levels, while in the Graphic 5.4 the starting point is knowledge that feeds the next nearest levels until coming to objectives and values which again influence knowledge.

Graphic 5.3

Graphic 5.4

There are three investigations with the Groups of Experience.

The first is with Students taking a course in the Social Problems, during the fourth year of professional studies in Sociology. The students already were grouped in ten groups according to the social problems chosen by each group. The objective was to place themselves first in terms of the problem and, afterwards, in terms of intervention. The instructions were: “Choose one area and only of the scheme, as a starting point for the definition of the problem. Starting from this place, successively link the other locations that you consider related. There can be areas that are not chosen in this process of definition”.

Four of the ten groups chose problems related to the transformation of the family and to women. All started from a point on the empiric level of knowledge, motivations and capabilities. The group that chose the problem of minorities did not draw any route between locations on the scheme; simply they drew a frame around the level of values, objectives and meaning. More clear, impossible.

The second experience is with social workers who had five to ten years of professional experience, during a “Workshop of reflection on frames of reference in their professional practice and intervention in the community”. The objective was to place themselves in relation to the diagnosis of a clinical case and, afterwards in relation to their intervention. What’s interesting is that the four groups show four different ways of positioning themselves in front of the possibility of analyzing their work from a professional perspective or from the user’s perspective. This result shows the lack of habit of defining in a conscious way from which place we contemplate the diagnosis or the intervention, something that it is difficult, but possible and even healthy to do.

The third experience was in reference to multidisciplinary work with a group of physiotherapist teachers participating in a summer course of the university on “Physiotherapy: A multidisciplinary task between reality and fiction”. Physiotherapists are a collective naturally well placed for a multidisciplinary approach. They spend a lot of hours with the patient, they find out about their life and work circumstances and have contact with medical specialists, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers, etc. Inter alia, presently there is pressure from the medical corporation to convert physiotherapy and rehabilitation into a medical specialty. Well, it is a long history.

This group of physiotherapist teachers not only manifested the symptom of their profession but also took on board the symptom of this thesis: That is, difficulties and obstacles in trying to achieve a multidisciplinary approach. There were four groups and they handed in four “routes” on the scheme we handed them, with the following four titles: “The case of the “physio-person-team”, “A case which does not happen often”, “An ideal route”, and “An imaginary case”. The positioning of the four groups highlights the reality of the fiction of this multidisciplinary profession and its very real deficiencies. Significantly, in the experience with the physiotherapists, the conference a medical member of the Articulating Group presented to the group was on “Pain”.

In conclusion

No ideology guarantees health, and conflict is not necessarily unhealthy. What is important is to become conscious of where we place the ideologies and where the conflicts, specifying options and accepting the fact that to make decisions is necessary unless we let circumstances decide for us.

For there to be a feeling of well-being, the symbolic system which determines our life experience needs a point of anchor, a guarantee, religious or not. In any case, some human beings have to occupy the place of the guarantor in facilitating the constructive processes and in controlling the transformation of the destructive effects of symbolic functioning.

An important problem is the part of the conflict which inevitably is unconscious or not conscious, and how to dominate it. The conflict cannot be eliminated like a virus is eliminated or the way we pretend eliminating any physical disease. We need room, spaces where in a regular and continuous analysis we question the conscious as well as the unconscious aspects of the conflicts which cause our anxieties. The thesis proposes places as well as methods of such an analysis, social spaces of health, where we can become aware of the schisms and over and over again articulate the new meanings, integrating the split off parts and recreate the feeling of well-being.